The rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI) feels eerily similar for those who lived through the internet boom of the 1990s. While every technological innovation is unique, the adoption and market excitement patterns follow a similar trajectory. Our macro framework for assessing AI outlines three waves of adoption, and in reviewing the internet boom, we have identified both parallels and some key differences.

One significant distinction can be seen in the foundation of today’s market leaders. Unlike in the 1990s, where many companies had sky-high valuations and minimal earnings, today’s leaders are largely grounded in strong business models. Therefore, we don’t see a similar 1999-style ending with stocks cratering. However, the similarities are more illuminating when examining the path ahead.

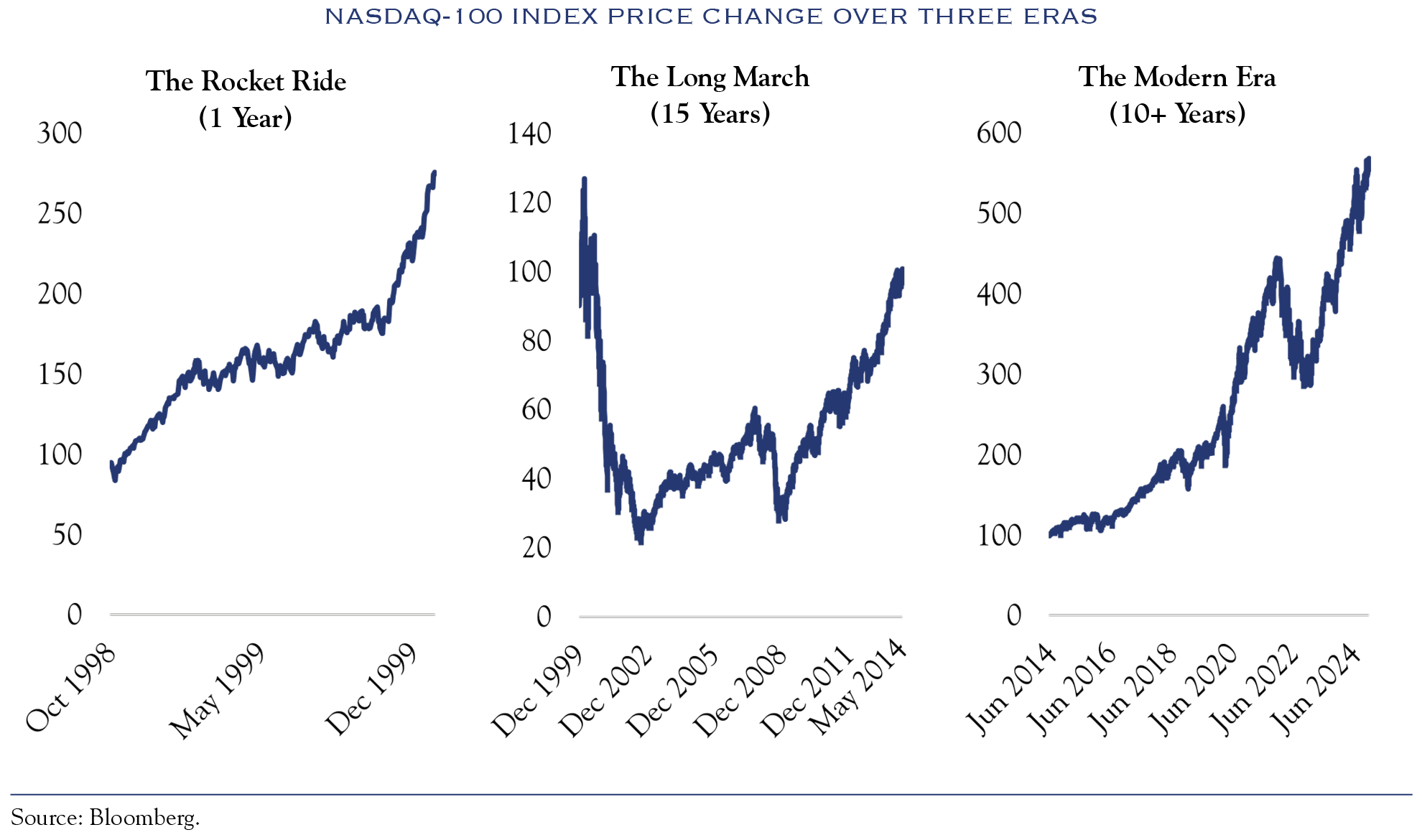

The Rocket Ride to the Modern Era

Our historical review involved segmenting different eras for the 1990s tech leaders. The first was “The Rocket Ride,” the period from October 1998 through December 1999 when anything internet-related soared in value. The second segment, “The Long March,” was the long stretch through a trough in December 2010 after the financial crisis, followed by a slow recovery thereafter, only reaching 1999 levels in 2014.

During the Rocket Ride, a wide range of stocks soared, as any connection to the internet was enough to boost investor interest and valuation. In this era, “normal” companies were left in the dust, particularly small caps.

However, when the rocket came back down to earth and the Long March started, small caps were at the top of the return ranking list, alongside some Rocket Ride winners who began to create solid business models (e.g., Amazon and Microsoft). Many first-movers simply collapsed and were sold for pennies on the dollar or went out of business.

Over the past 15 years or so, strong business models have again carried the day, with Amazon and Microsoft once more leading the way. However, large-cap growth stocks and even small-cap stocks have outperformed many surviving original winners, like Cisco or Intel, which continued to post lackluster stock gains.

Over the long term, the real winners were those companies that leveraged the technology to post earnings gains, sometimes through revenue expansion, sometimes through cost advantages, or a combination of the two.

History shows that first-mover advantage only lasts a short time. While early investors who timed the Rocket Ride perfectly could reap the rewards before the collapse, this is neither reasonable nor sustainable as an investment strategy. Over the long term, the real winners were those companies that leveraged the technology to post earnings gains, sometimes through revenue expansion, sometimes through cost advantages, or a combination of the two.

Riding the Waves

With AI, we expect to see three waves, ultimately culminating in advantages to those who use the technology for cost and productivity advantages, thereby expanding profit margins relative to peers.

- The first wave is well underway, with chipmaker Nvidia leading the charge. There is often a race into the “picks and shovels” of a tech revolution, which is clearly happening here.

- The second wave is also underway, with early adopters mostly seeking a revenue boost or a competitive advantage in their product offerings. These are the companies creating Large Language Models (LLMs) or incorporating similar technology into existing offerings. OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Meta are all prominent examples.

- The third wave has only barely begun, but it is where we expect to see the greatest progress and, eventually, earnings gains and possibly capital appreciation. These are companies that will utilize technology that has already been built by others. They will seek efficiency gains and margin expansion. We believe AI will predominantly become a long-term efficiency tool via expanded productivity.

Our thesis is that companies that have invested in AI tools and training will begin to see higher productivity, allowing them to expand business (increase revenue) with smaller staffing increases than companies that chose not to utilize AI.

The biggest battleground here will be the return on investment from expenditures in AI. Our thesis is that companies that have invested in AI tools and training will begin to see higher productivity, allowing them to expand business (increase revenue) with smaller staffing increases than companies that chose not to utilize AI.

A Model for AI

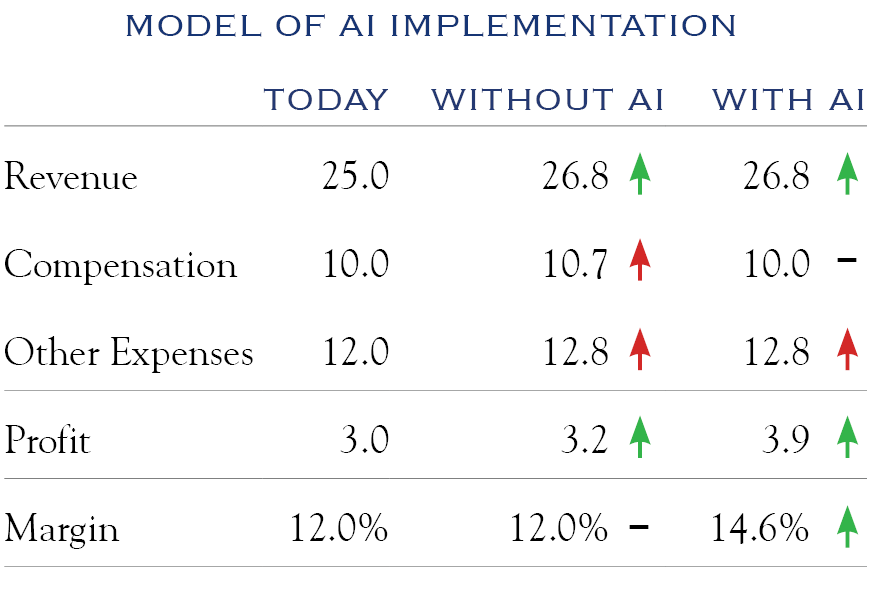

In the model below, we form estimates of revenue, compensation, and profit margin; the results are designed to be similar to those of U.S. equities and the economy overall. While there is a case to be made that AI can also be additive to revenue, that AI can find other efficiencies in the cost structure, and that robotics play a role, those have been excluded here. This model is simple by design and meant to demonstrate the divergence between productivity improvers and status quo companies; it is meant to be illustrative, not specific.

Our model shows that a company implementing AI sees an increased profit margin, as it can increase staffing at a lower rate than revenue.

We estimate this benefit as handling a 7% revenue increase with no staffing change, assuming that AI provides a 14% productivity boost to 50% of the workers. This is a reasonably conservative assumption. Our estimate is based on findings from one of the more extensive AI studies to date by Eric Brynjolfsson. A more pessimistic survey came from Daron Acemoglu, which pegged the productivity gain at 5%, while one of the most optimistic estimates was from Vinod Khosla, who predicted AI would handle 80% of the work in 80% of jobs.

We expect increased dispersion as some companies succeed in becoming more productive and profitable while others

fail to adapt to these very powerful forces.

Brynjolfsson coined the phrase “productivity J curve,” noting that technological advances take time to show up in productivity and profits. Brynjolfsson also said in a recent Wall Street Journal article: “This is a time when you should be getting benefits and hope that your competitors are just playing around and experimenting.” Gains from AI will vary by industry and depend on how well companies implement change that unlocks productivity. We expect increased dispersion as some companies succeed in becoming more productive and profitable while others fail to adapt to these very powerful forces.

If the gains from AI come mainly from incremental efficiency, this should be an advantage to expanding companies. In our estimation, the path to AI usage does not allow easy staffing cuts. However, the productivity boost should allow more business (revenue) to be done by the same number of employees. This approach is also easier to implement and more politically and societally palatable.

The road ahead for AI is the story of implementing technology to boost productivity and margins. This will place a higher-than-normal burden on management teams’ qualitative interpretation. It won’t happen overnight, but it will drive dispersion between those who adapt and those who don’t.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Teeter. No part of Mr. Teeter’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC