Free Trade, Then & Now

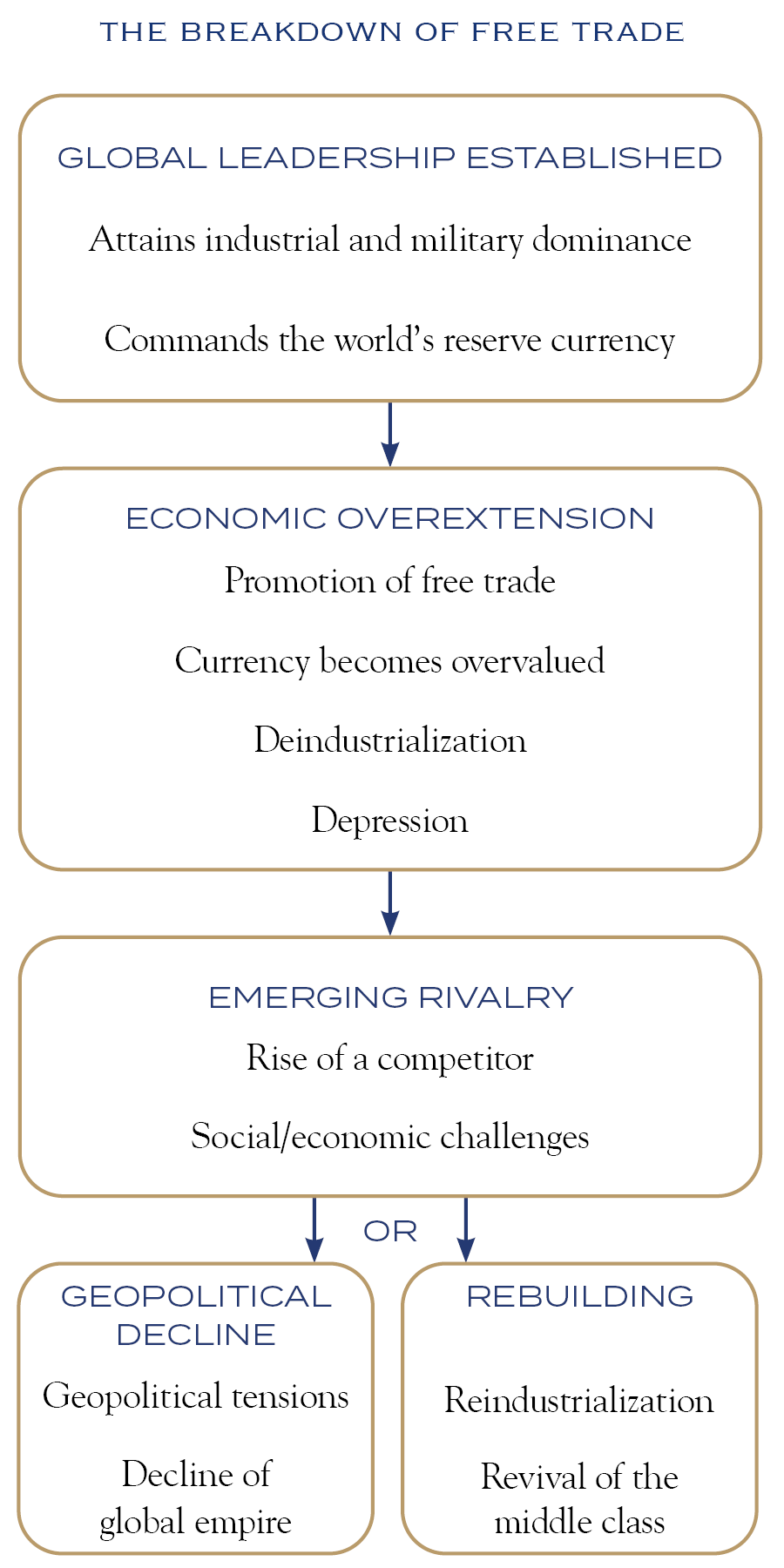

Imagine that the most powerful country in the world shifts its focus from manufacturing to finance while promoting free trade. The country subsequently deindustrializes as factories and jobs are outsourced to nations with cheaper labor. Initially, many benefits are realized, including cheaper goods for end consumers. But reality sets in. A growing displaced labor pool is accompanied by a prolonged economic downturn. Meanwhile, another country invests in factories, technical education, and exports, sparking explosive growth. The once undisputed economic champion of the world realizes its missteps, and tensions rise with the upstart competitor.

While this scenario resembles today’s saga of U.S.-China relations, it actually describes the economic rivalry between the United Kingdom and Germany from 1846 to 1914.

While this scenario resembles today’s saga of U.S.-China relations, it actually describes the economic rivalry between the United Kingdom and Germany from 1846 to 1914. While these sorts of pivotal events unfold more rapidly in today’s world, the underlying economic and political dynamics remain strikingly similar.

Britain’s Industrial Dominance & Naval Supremacy

Following Napoleon’s fall at Waterloo and the Congress of Vienna in 1814, Britain emerged as the world’s leading industrial and naval power. Technological innovations such as the steam engine and railways bolstered its dominance, with British factories producing two-thirds of the world’s coal and half of the world’s iron by the mid-19th century. Meanwhile, Britain’s naval supremacy allowed it to control global shipping routes and solidify its position as the preeminent economic and financial power, with the pound sterling functioning as the world’s reserve currency. As we will see, reserve currency status, national security and free trade are intertwined.

The Rise of Free Trade & Britain’s Industrial Decline

By 1873, concerns over economic stability led to a depression, highlighting the detrimental effects of prioritizing free trade over industrial investment.

As financial interests in London grew, British policies increasingly favored global trade over domestic industry. In 1846, the repeal of the Corn Laws—protectionist tariffs on imported grains to protect domestic agriculture—marked a shift toward “absolute free trade,” initially lowering food prices but ultimately devastating local agriculture and exacerbating wealth inequality. By 1873, concerns over economic stability led to a depression, highlighting the detrimental effects of prioritizing free trade over industrial investment.

During this period, foreign investors began to question the viability of Britain’s economy. The Bank of England, controlled by London’s financial elites, raised interest rates to lure gold back to its vaults, further harming Britain’s domestic industries. The lack of capital investment in manufacturing became evident as German industries surged ahead.

Germany’s Rise & the Breakdown of Free Trade

Germany recognized the flaws in Britain’s free trade model and adopted protectionist policies. It invested heavily in internal trade, technical education, and tariffs to support its flourishing yet nascent industries. By the turn of the century, Germany had surpassed Britain in steel production and emerged as a leader in the electrical and chemical sectors.

As Britain’s industrial base eroded, it became vulnerable to rising powers. The U.K. altered its foreign policy by abandoning its 19th-century alliances aimed at preserving the Ottoman Empire as a barrier against Russia. Instead, it forged the Triple Entente with France and Russia to counter German expansion.

The Outbreak of World War I, the Fall of the British Empire & The Rise of the U.S.

By the early 20th century, two German developments alarmed Britain. First, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria, built a modern fleet for protection against Russia and France. He offered limits on his High Seas Fleet in exchange for Britain’s neutrality, but Britain refused. Then, he proposed a Berlin-Baghdad railway, enhancing German access to oil and reinforcing its imperial ambitions. Despite multiple German offers to co-finance the railway, Britain refused and instead occupied Kuwait to block German access from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf.

Tensions culminated in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, igniting the geopolitical rivalries that led to World War I. The war devastated Europe and accelerated Britain’s industrial decline.

Britain was already financially strained and struggling to compete with newer industrial powers. By the war’s end, Britain faced nearly one million deaths, massive debts, and a hollowed-out industrial base, signaling the decline of its imperial hegemony. The U.S., though initially neutral, profited from wartime production and emerged as a global financial center.

Free Trade 2.0 & the Decline of U.S. Industry

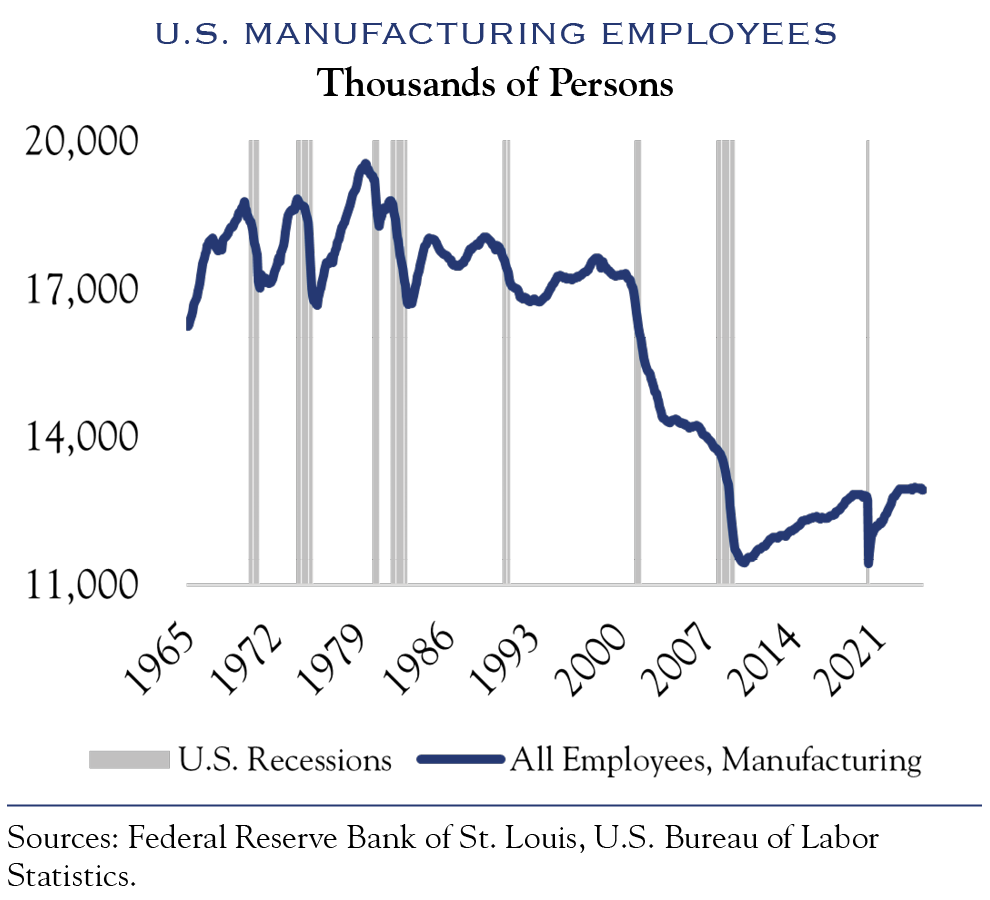

Fast-forward to the 21st century, the parallels between the U.S. and China are striking. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 sparked a “China Shock,” which led to lower consumer prices and increased corporate profits. However, this came at a significant cost: the U.S. lost 25% of its manufacturing workforce, equating to 4.5 million relatively high-wage jobs. Many more non-manufacturing jobs that depended on local manufacturing economies were lost as well.

The outsourcing of jobs primarily affected key industries like automotive, textiles, steel, and electronics, which shifted production to countries with lower labor costs. The Rust Belt, a region once dominated by manufacturing, was especially impacted as factories closed or downsized due to increased global competition. This wave of offshoring significantly eroded America’s industrial base, leaving many communities economically weakened.

This decline in industrial capacity and the loss of human life mirrors the consequences of a lost war, similar to what Britain experienced a century earlier.

The loss of industrial capacity resulted in rising economic despair and loss of purpose, leading to profound social and economic consequences. Since 2010 alone, the CDC reports over 800,000 Americans—particularly young men—have died from drug overdoses, a figure higher than the combined deaths of all U.S. soldiers in 20th-century wars. Suicide rates rose by 37% between 2000 and 2022, totaling nearly 50,000 Americans annually. Americans over 16 years of age with a disability have risen from 26 million in 2010 to 34 million today. While there’s no straightforward correlation between middle-aged death rates and economic conditions, the disproportionate share of these deaths in the economically distressed Rust Belt underscores the region’s significant challenges. This decline in industrial capacity and the loss of human life mirrors the consequences of a lost war, similar to what Britain experienced a century earlier.

The U.S. didn’t just lose its industrial base but also saw the decline of its telecommunications leadership. Lucent Technologies, originally known as Bell Labs, had been a global pioneer, driving breakthroughs like the transistor and fiber optics. However, after its acquisition by French-based Alcatel in 2006, followed by Alcatel’s acquisition by Nokia a decade later, the U.S. had lost its dominant position. This shift became a national security concern when Huawei emerged as the leader in 5G development. In 2019, the U.S. and its allies restricted their companies from selling technology, software, and components to Huawei without government approval to prevent China from gaining control over critical global communication networks.

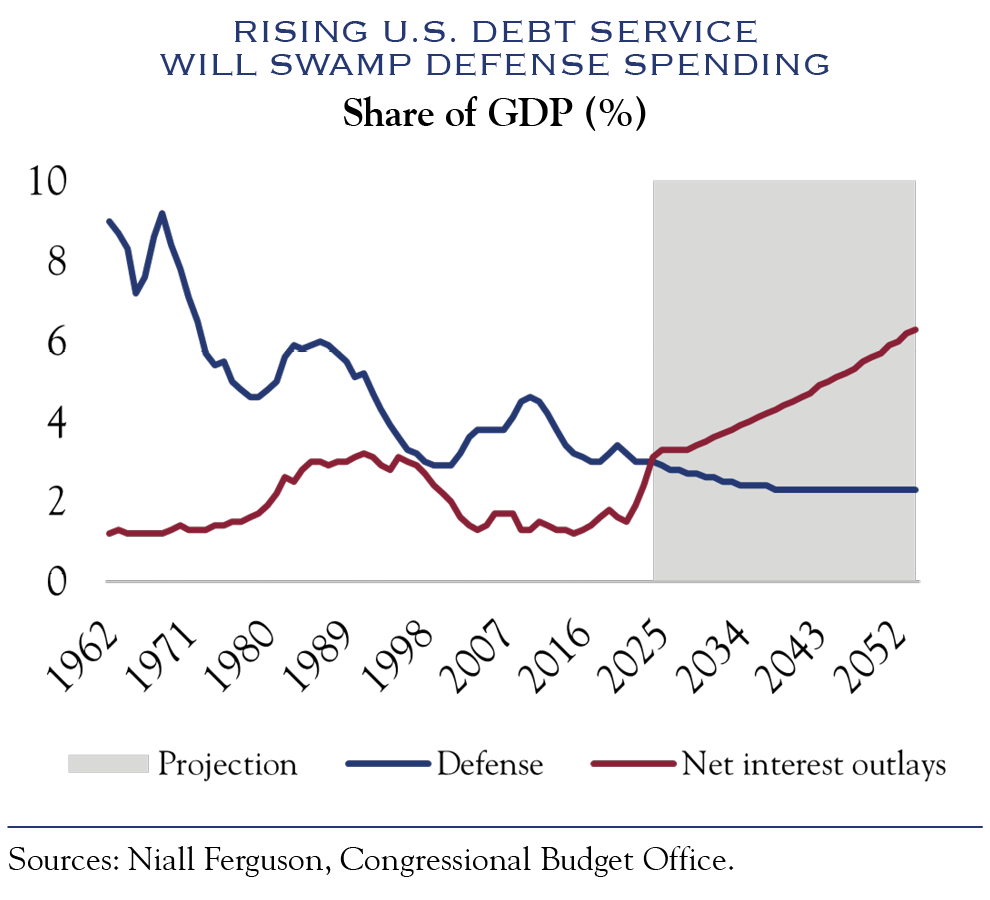

What’s more, historian Niall Ferguson’s “Ferguson’s Law” warns that “any great power that spends more on debt service than on defense will not stay great for very long.” He argues this was true of Hapsburg Spain, ancien régime France, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire. The U.S. has now crossed the Rubicon. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that FY24 net interest outlays are at 3.1% of GDP, above defense spending at 3.0%, while they project that interest payments will be double what we spend on national security by 2041.

The Breakdown in Free Trade 2.0

The U.S. dollar, as the world’s reserve currency, remains persistently overvalued. About 60% of the $12 trillion in global foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. dollars, creating inelastic demand that inflates its value. This overvaluation disproportionately impacts the U.S. manufacturing sector, making American-made goods more expensive on the global market.

While discrepancies in purchasing power parity (PPP) may have a limited impact in peacetime, they become crucial during times of conflict. In the ongoing war in Ukraine, for example, Russia is outproducing NATO in key military components like battle tanks, artillery shells, rockets, and hypersonic missiles. This is largely due to Russia’s lower production costs, which are made possible by a more favorable exchange rate. Similarly, China has produced a wide range of critical manufacturing products—from semiconductor factories and nuclear power plants to electric vehicles, lithium refineries, and military weapons—at a fraction of the cost of producing them in the U.S.

In response to the erosion of U.S. manufacturing and the subsequent growth of the trade deficit with China, both Presidents Trump and Biden implemented measures to reverse the trend, such as tariffs on Chinese goods and initiatives like the CHIPS and Science Act. However, reshoring efforts face significant challenges. High costs and policy uncertainty have delayed some 40% of the largest onshoring projects. Investors and consumers have welcomed the easing of inflation, but a key factor behind this is the significant slowdown in the U.S.’s efforts to reshore its defense and industrial base.

For the U.S. to successfully reshore its manufacturing base, it will need to reassess its strategies on global trade, currency, and national security.

For the U.S. to successfully reshore its manufacturing base, it will need to reassess its strategies on global trade, currency, and national security. This includes finding ways to reclaim some of the advantages other nations enjoy due to the U.S.’s responsibility to finance the global reserve system and provide a defense umbrella. Currently, the U.S. has the lowest tariff rate in the world, at just 3%, compared to 5% in the E.U. and 10% in China. With President Trump returning to office, it seems likely he will not only seek to deregulate parts of the economy but also use tariffs as a tool to boost American manufacturing competitiveness, signaling the breakdown of free trade for this cycle of history.

Concluding Thoughts

The global economic landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, marked by the gradual decline of free trade and the emergence of a multipolar world. While the U.S. remains the dominant power in terms of global influence, we are witnessing a shift away from the post-Cold War era of U.S.-led globalization.

History demonstrates that the pendulum between free trade and protectionism swings with the tides of industrial and geopolitical change. While free trade offers certain benefits, it becomes problematic when a nation’s currency strengthens to the point where its industries struggle to compete globally. The U.S. faces this challenge today, but it can avoid the mistakes made by Britain if it successfully rebuilds its industrial base.

When Britain could not compete with Germany in the early 1900s, it greatly contributed to the tensions that ultimately boiled over into 30 years of global war. The resurgence of U.S. manufacturing is not only a matter of economic recovery but also a strategic imperative to avoid the geopolitical tensions that arise from economic dependencies on foreign supply chains. A gradually and orderly weakened dollar, though contributing to inflationary pressures, will stimulate domestic manufacturing and help the U.S. regain its middle class as well as its competitive edge on the global stage.

What we can take away from this as investors of capital is the following: The breakdown of free trade in the 20th century led to the outperformance of real assets over financial ones, coupled with higher inflation and a decline in the real value of the British pound as well as its sovereign debt. As we are experiencing a similar decline in free trade today, we anticipate similar outcomes. In addition to a weaker dollar in relation to real assets, we believe an actively managed, globally diversified portfolio will be critical for navigating the challenges and opportunities ahead.