What Are The Twin Deficits?

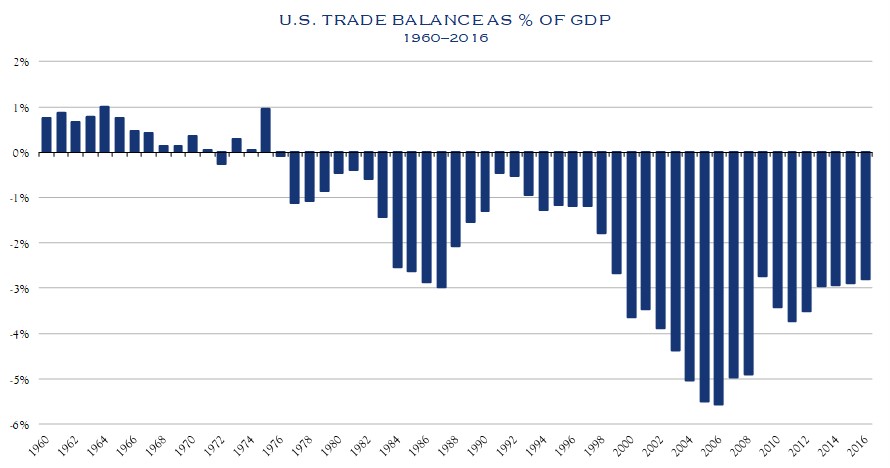

The Twin Deficits are the federal budget deficit and the trade deficit. Both have been salient features of the U.S. economy for several decades and are more closely connected than many people appreciate.

Why Talk About Them Now?

The downward pressure that has kept U.S. share prices flat so far this year, despite strong earnings growth, is due to concerns arising, at their heart, from the Twin Deficits. There are worries that a larger budget deficit, due to recent tax cuts, will overstimulate the economy, giving rise to inflation and higher interest rates. And there are worries that, in his determination to shrink the trade deficit, President Trump will take steps that risk unleashing a trade war.

Will A Larger Budget Deficit Lead To Higher Inflation And Interest Rates?

When the economy is at full employment and doesn’t have much slack, it’s certainly possible that a larger budget deficit will compete with the rest of the economy for capital, and that the demand it creates just bids up prices. But in an economy like the U.S. that’s open to foreign trade and capital flows, there’s another way this can play out. The debt can be financed by capital from abroad, and the demand it creates can be satisfied by output from abroad—a larger trade deficit. That’s what happened in the 1980s: a larger budget deficit caused a larger trade deficit, even as inflation and interest rates fell.

How Are The Two Deficits Connected?

People often think that trade imbalances are caused by differences in competitiveness, but that’s not true. A country that’s more competitive, more productive and that produces more, can also spend more, enjoy a higher quality of life and import just as much as it exports.

The downward pressure that has kept U.S. share prices flat so far this year, despite strong earnings growth, is due to concerns arising, at their heart, from the twin deficits.

A country that’s less competitive will produce less and also has to spend less unless someone is willing to lend it the money to spend more. Trade surpluses happen when one country doesn’t want to spend as much as it produces—when it has more savings that it needs—and is willing to lend money to another country, which can now spend more than it produces and run a trade deficit. So, trade surpluses and deficits are really about savings—about lending and borrowing—not competitiveness.

Government budget deficits are part of national savings. When Washington runs a larger budget deficit, national savings goes down. In a closed economy, interest rates must go up until households save more (and consume less) and fill that gap. In an open economy, the needed savings can come from abroad instead, and as a result we end up running a larger trade deficit.

Is This A Good Or Bad Thing?

It is neither good or bad to lend money or borrow it. It really depends where the best returns on investment are. When a company borrows money to build a factory, or a student borrows money to go to college, the money, if used wisely, can boost future income and be paid back no problem. If it is spent on things that don’t enhance or even detract from a future earnings capacity, it’s a problem. If you’re lending money—running a surplus—you have to care what the borrower is doing with that money as well, or your “savings” will disappear down a hole.

Trade surpluses, and deficits, are really about savings, about lending and borrowing, not competitiveness.

Is The U.S. Borrowing Wisely?

That’s really the critical question, and the answer isn’t encouraging. Republicans and Democrats disagree about what policies—tax cuts to spur private investment or spending on social resources—would best boost productivity. It’s a debate that’s worth having, but it’s increasingly shoved aside.

Source: Bloomberg

Even before the recent tax cuts, the federal budget deficit was already above its historical average, and expected to rise to 5.2% of GDP by 2027. The main driver is entitlements, which are consumption, not investment. In the 1960s, the federal government spent $3 on productivity-boosting public investments, in infrastructure and scientific research, for every $1 on more consumption-oriented entitlements. Today, that ratio has flipped. We obviously want health care, retirement benefits, etc., but borrowing to pay for them—and funding it from abroad—is problematic.

What Does This Mean For Investors?

There are two questions here: What does it mean for the current business cycle and our near-term expectations? And what does it mean for our longer-term return expectations?

We’re at a point in the business cycle where price pressure could pick up, and interest rates will likely rise in response, but larger budget deficits probably won’t be as big a factor as feared.

In the near-term, the relationship between the Twin Deficits means that market worries that recent tax cuts will automatically translate into higher inflation and higher interest rates are likely overblown. We’re at a point in the business cycle where price pressure could pick up, and interest rates will likely rise in response, but larger budget deficits probably won’t be as big a factor as feared. Larger budget deficits could, however, translate into a wider trade deficit, fueling calls to “fix” it by adopting trade sanctions. But tough trade measures that don’t really address the underlying issue—the mix between consumption, savings, and investment, both at home and abroad—are likely to do more harm than good.

The fact that the U.S. is borrowing to spend, rather than invest, is an issue that definitely weighs on our longer-term outlook, as unproductive spending is a drag on growth. Addressing this—or failing to address this—might not make much of a difference in the current business cycle, but takes on greater significance when we begin to look past this cycle.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Chovanec. No part of Mr. Chovanec’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC