“Happy days are here again!” At least, that’s how investors are feeling after a year that saw total returns (including dividends) of +31.5% for the S&P 500. Fears of recession risk, Brexit, and trade wars, which drove a steep sell-off at the end of 2018, seem to have suddenly receded like a bad dream, pushing stocks to new heights.

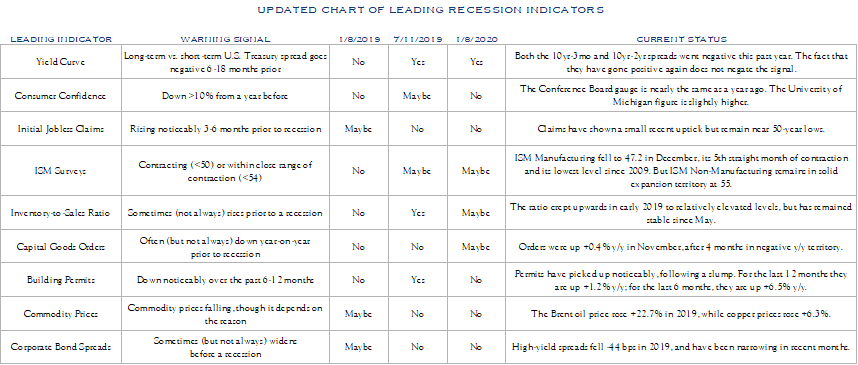

Yet how much has really changed? The U.S. economy has slowed, and possible recession indicators remain mixed. Most U.S. tariffs against China remain in place, we’ve disabled the World Trade Organization (WTO), and new measures aimed at Europe are possible. Global manufacturing, including in the U.S., is in contraction. U.S. corporate earnings have hit a slow patch as the effects of a major tax cut and a surge in share buybacks begin to fade.

One thing that has changed is the Fed. In late 2018, markets feared the Fed would continue raising interest rates one time too many and help push the economy into recession. Instead, freed by low inflation, the Fed cut rates three times, and even began expanding its balance sheet again—though it denies a full-fledged return to Quantitative Easing (QE). In August, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries dipped back to near-record lows, and a third of all investment-grade bonds around the world—$17 trillion—had rates below 0%. Those extremes have since subsided, but the persistence of low inflation and low interest rates—and high relative rewards for equity risk—is likely to continue bolstering market performance in the year ahead, despite otherwise choppy seas.

How Long Can You Go?

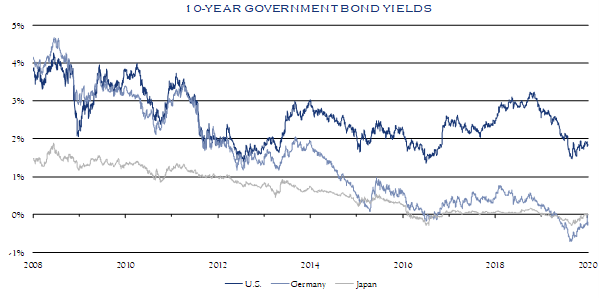

Few expected interest rates to remain so low for so long. When the Fed cut its benchmark overnight funds rate to virtually 0% in December 2008, it was expected to be an emergency and temporary measure. Instead, it lasted seven years, until December 2015. The persistence of this “new normal,” along with $3.6 trillion in bond purchases by the Fed, gradually pulled 10-year U.S. Treasury yields below 1.5% by mid-2012. When, in late 2013, the Fed announced it would reduce and eventually end bond purchases, the 10-year rate rose to 3.0%, which most took as a harbinger of even higher rates to come. Instead, longer-term rates languished. Even after the Fed began raising the funds rate, an economic slowdown in mid-2016 helped push the 10-year Treasury yield to an all-time low of 1.37%. This year, in response to a new round of recession fears, the Fed began cutting rates again. While the 10-year yield, which ended the year at 1.92%, has bounced back a bit from its latest plunge, it ended the year 77 basis points lower than it began.

For as long as they’ve been around, economists have maintained that interest rates cannot go below zero. Since cash is a government note that earns 0%, the thinking went, a saver would always pull his/her money out of a bank account or security yielding −0.01% and hold it in physical currency instead. The problem is that’s really not practical for large sums. If the central bank of a reasonably stable country starts charging banks on their excess reserve deposits, instead of paying them interest, there’s not much they can do. They might well be willing to lend or invest that money at negative rates in order to avoid an even higher charge. That’s precisely what the European Central Bank (ECB) started doing in 2014, followed by the Bank of Japan (BOJ) in 2016. The result has been to pull short-term and eventually long-term sovereign bond yields for Germany and Japan into negative territory. This fall, one bank in Denmark began offering 10-year fixed interest mortgages at a rate of −0.5%; in other words, they’ll pay you to buy a house. One alternative, for savers abroad, is to invest in U.S. assets still offering positive yields, which puts downward pressure on U.S. rates as well.

Source: Bloomberg

It’s easy to credit—or blame—central banks for these policies. It’s far from clear, however, whether central banks are the dog wagging the economy as its tail, or the other way around. Central banks can fix certain short-term rates, but their influence over longer-term rates is only indirect. Ultra-low long-term bond yields suggest that there are enough investors out there convinced that the economic outlook is fragile enough to force central banks to keep rates low—and that inflation will remain low enough to allow them. They might even suggest that some investors would prefer to lose a small amount of money on a “safe harbor” security than (they fear) lose a larger amount on a riskier investment like stocks. Having the central bank buying bonds can reduce the number of investors required to feel this way, but some, at least, must be willing to pay a very high premium for safety. In many ways, the Fed and other central banks are responding to this reality, not simply creating it. When U.S. 10-year yields fell to record lows in July 2016 and August 2019, it was long after the Fed had stopped buying Treasuries.

Give Me A Boost

There are two rationales for the central bank to cut short-term rates. First, lower rates make it cheaper for people to borrow money to spend or invest, reviving economic growth. Low rates, in recent years, likely played an important role in financing the shale fracking boom in the U.S., in the face of large recurring capital requirements and uncertain returns. Evidence suggests that the Fed’s latest rate cuts have given a boost to the U.S. housing market, which had been in a slump since early 2018.

The second rationale—a central one behind QE—is to boost asset prices. When interest rates fall, they cause the value of existing debt securities—promising a fixed rate of return—to rise. The impact of low interest rates on other asset prices is more complicated, because it depends on growth expectations. The value of most assets—whether it be a factory, a home, or a share of stock—is a function of their expected return versus the opportunity cost of safely earning interest instead. If interest rates fall, asset values will rise—unless rates are falling because the economy is weakening and expected returns are falling as well. If interest rates rise, asset values will fall—unless rates are rising because the economy is improving and expected returns are rising as well.

The architects of QE hoped that, by making people feel wealthier, they would go out and spend more. They would also be pushed to invest in riskier assets if they wanted to earn a decent return, reducing the cost of capital for businesses to invest. The resulting growth would end up justifying those higher asset prices, even as interest rates eventually returned to normal. Critics, on the other hand, argued that QE and ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) were propping up an asset bubble, and that as soon as they stopped, stock market and other prices would come tumbling down.

In our view, these fears were overstated. Growth did return, whether aided substantially by low interest rates or not, boosting share prices. P/E valuations also rose, as they normally do in the upward phase of a cycle. But an elevated Equity Risk Premium indicates they rose far less than competing interest rates fell. Far from gorging on risk, investors have been strikingly risk-adverse throughout this bull market, demanding a higher level of equity returns, compared to the prevailing interest rate, than normal. Low interest rates may have been supportive of equity valuations, but not recklessly so.

That’s not to say that ultra-low interest rates, for a lengthy period of time, have been free of any downside. The boost to asset prices from lower rates, a growing chorus of critics point out, benefits wealthy investors first and foremost, in the hope—possibly misplaced—that it will “trickle down” to help everyone else. And while higher asset valuations, relative to earnings, translate into immediate gains for existing owners, for new buyers it means those assets are more expensive, promising a lower rate of return. This makes it harder for savers to earn enough for retirement, or for entities like insurers and pensions to meet their obligations—a particular problem in developed countries with aging populations. Low rates may encourage companies to buy back shares, arguably diverting funds from more productive investments, and have pushed corporate debt levels to a new high, 48% of GDP. Highly leveraged companies, and even whole industries like shale fracking, may become dependent on the ready availability of cheap credit, and vulnerable if interest rates ever do rise. For all that, growth has remained sluggish and uneven throughout this recovery, with little sign of being able to support a return to higher interest rates.

All of these issues have sparked a growing backlash among economists and politicians against ultra-low rates as a cure-all for economic anemia, and a shift in focus towards other forms of stimulus, including fiscal spending. President Trump may have called, in a recent tweet, for the Fed to “get our interest rates down to ZERO, or less” in competition with Europe and Japan—a comment that got many Americans talking about the prospect of negative rates—but we think it is unlikely the Fed is eager to go down this route, even in the event of a recession. Whether there is the political will or consensus to enact some form of fiscal stimulus instead—in the U.S., Germany, or Japan—remains to be seen, but is likely to become a more prominent topic of debate if the global economy continues to slow.

In the meantime, however, interest rates are likely to remain low. Sluggish global growth and burgeoning energy supplies have kept inflation below target, with the PCE price index hovering at just +1.5% y/y. New tensions in the Middle East, between the U.S. and Iran, could push oil prices up if they spin out of control, or tighter labor markets could begin to spill over into rising cost pressures. So far, however, continued hiring—and record low layoffs—has translated into real wage growth, not broader inflation. As a result, the Fed is under no immediate pressure to reverse course and begin tightening again. To the contrary, the Fed’s efforts to unwind its QE bond holdings appear to have had a disruptive effect on liquidity in some credit markets recently, prompting the Fed to start expanding them again. Though the Fed insists this is a technical fix that does not signify a return to QE, some have taken it as such. Commentators have noted that, for every +1% rise in the Fed’s balance sheet since October, the S&P 500 has gained about +1%. In sharp contrast to a year ago, when they feared an overly aggressive Fed would tip the economy into recession, markets appear to be taking reassurance from what they see as a benign Fed.

Not Out of the Woods

That’s important, because despite the shift in sentiment, the economy isn’t entirely out of the woods yet. The New York Fed is projecting +1.2% GDP growth for Q4, down from +2.1% in Q3. Some better-than-expected data in recent months has boosted the Atlanta Fed’s Q4 projection from a dismal +0.3% to a more encouraging +2.3%. Either of these projections will result in an annual GDP growth figure of +2.3% for 2019, down from +2.9% in 2018.

The slowdown, both at home and abroad, is concentrated in manufacturing, and does not appear to be letting up there quite yet. The ISM Manufacturing Index fell −0.9 in December to 47.2, its fifth straight month in contraction and its lowest level since June 2009. (Purchasing manager surveys also show manufacturing in Germany and much of the Eurozone, as well as Japan, in a sustained contraction). Durable goods orders fell −2.1% in November, down −3.8% from a year ago, while freight shipments by truck, rail, air, and barge were down −3.3% year-on-year. In one potential bright spot, core capital goods orders rose +0.2% in November, pushing them back into positive territory year-on-year, after four months in the red signaled a possible recession risk.

Despite these headwinds, the economy continued to add new jobs at a steady pace, an average of +180,000 per month through November, down from +223,000 for all of 2018. Even manufacturing jobs grew at rate of +6,000 per month, albeit a noticeable step down from +22,000 the year before. As a result, U.S. consumers remain confident and willing to spend. Personal incomes were up an impressive +4.5% in November, compared a year ago, and consumer spending was up a solid +3.9%. Auto sales have struggled, and likely fell below a benchmark 17.0 million in 2019, but lower mortgage rates helped prompt a highly visible rebound in the U.S. housing market. New home sales in November were up a striking +16.9% from a year ago, while new housing permits—which raised possible recession flags last year by falling into negative territory—were up a vigorous +10.5%. Unlike its manufacturing counterpart, the ISM Non-Manufacturing gauge—which covers a much larger portion of the economy—rose +1.1 points in December to 55.0, reflecting continued growth momentum.

Fed rate cuts have helped curb the dollar’s climb, which in turn has helped stabilize the U.S. trade deficit. While markets may welcome the anticipated signing of a “Phase I” trade deal with China and ratification of the revised NAFTA agreement with Canada and Mexico, we are skeptical that trade peace is about to break out. The deal with China is mainly a ceasefire; even if it holds, most tariffs remain in place, and there are plenty of sore spots in the relationship that will continue to create trouble and uncertainty. U.S. moves to disable the WTO’s dispute resolution mechanism may prevent it from striking down recent U.S. trade measures, but could lead to more trade friction globally—a particular concern for Britain, which is looking to WTO as its lifeboat in case of a no-deal Brexit. The U.K.’s recent election cheered markets by giving the appearance of some sort of decision on Brexit. In fact, all of the tough choices still need to be made; Johnson’s “decisive” victory just means they can’t be put off much longer.

Amid these uncertainties, U.S. corporate earnings have hit a slow patch. After-tax corporate profits in Q3, for the economy as a whole, were down −1.1% from a year ago. S&P 500 quarterly operating earnings per share (EPS) in Q4 are expected to up be up +14.7% from a year ago, but only because of a precipitous fall in Q4 the previous year; in fact, they are expected to be little changed from Q3, when they were down −3.8% y/y. For 2019 as a whole, EPS should be up about +4% from 2018, boosted in part by record share buybacks in the first half of the year. But this masks uneven results: six out of 11 sectors saw year-on-year declines, and only two—health care and financials—saw significant earnings growth. Rising share prices have somewhat outpaced earnings growth and are expected to push the 12-month trailing P/E ratio for the S&P 500 to 20.4x, its highest quarter-end level in three years. This rise in equity valuations, along with the latest rebound in 10-year Treasury rates, has narrowed the Equity Risk Premium from 5.9% in June to 5.2% at year-end, though this remains well above the long-term historical average of 4.2% and continues to favor exposure to equity risk.

We may not be ready to pop any champagne bottles, but the past year’s stock market gains have been testament to the importance of maintaining perspective and discipline in the face of uncertainty. Growth has slowed, and the economic outlook remains mixed, but the persistence of low inflation and low interest rates is a supportive factor to both the economy and markets that no investor should ignore. They help explain why markets are riding high, even if the economy isn’t.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Chovanec. No part of Mr. Chovanec’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC