Fear of heights. It can be either rational or irrational. The irrational kind, called acrophobia, often arises from some traumatic experience, and can spark debilitating panic even at relatively safe heights. However, even the entirely rational version, called basophobia, can trigger an interesting reaction called astasia-abasia: an instinctive need to crouch, and aversion to standing erect. You may have experienced this. I know I have.

The stock market, in recent months, has been crouching along close to all-time highs, flinching from time to time at the view below. Early in this recovery, much of the fear was irrational, informed by proximity to the 2008 financial crisis. Now, more than 10 years into a bull market, the concern is more rational. The growing weakness of recent economic data at home and abroad, as well as the potential for unsettling shocks ahead, cannot be ignored. Yet given the relative prices for safety and risk in today’s market, investors should resist the urge to cower.

Slowing Down

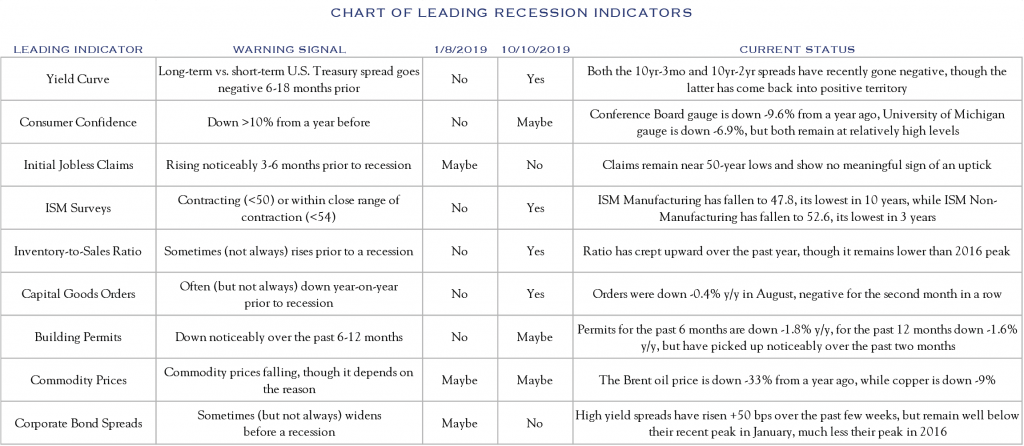

The U.S. economy has certainly slowed down, and it may be catching a bit of a cold. Although some of our “leading indicators” of a possible recession (see appendix) have improved since the start of the year, a majority have drifted from “no” to slightly “yes”. Nothing has fallen off a cliff, but several have either stagnated or weakened. The ISM Manufacturing Index fell −1.3 points in September to 47.8, its lowest reading in 10 years and its second month in contraction. The ISM Non-Manufacturing Index fell −3.8 points to 52.6, its weakest expansion reading in three years. Both are stark declines from their strong >60 readings last year. Durable goods orders in August were down −3.0% from a year ago. Orders for core capital goods—a key indicator of business investment—leveled off last summer and are down slightly (−0.4%) from a year ago. Inventory levels have been creeping upwards, outpacing sales.

Even consumer confidence has come down noticeably from its previous record highs, though it remains quite strong, bolstered by continued hiring and income growth. The economy has added an average of +161,000 jobs per month so far this year—down from +223,000 last year, but still a decent pace. Initial jobless claims, which usually tick upwards going into a recession, remain near 50-year lows. Personal income is up a striking +4.6% from a year ago, while consumer spending is up a solid +3.7%. Retail sales have risen in seven out of eight months so far this year, and in August were up +4.1% from a year ago. The PCE price index—anchored by lower energy prices—is up just +1.4% from a year ago, giving consumers more real purchasing power. Modest inflation has also given the Fed room to cut interest rates twice this summer, which seems to be lending some new life to the struggling housing market. New housing permits—a possible recession indicator that, over the past 12 months, has been down −1.6% from the previous year—were up +12.5% year-on-year in August.

As a result, the Atlanta Fed currently projects U.S. GDP growth of +1.7% in Q3, while the New York Fed projects +2.0%—hardly thrilling, but not a recession. In late 2015 and early 2016, the U.S. saw a similar manufacturing slump, due to a strong U.S. dollar and a collapse in oil prices. We discussed the possibility of a recession, at the time. But the U.S. consumer, bolstered by steady job growth and low inflation, kept spending and the broader economy pulled through. Whether that can happen again is the key question, at least short-term. It’s complicated by a number of disruptive events that, depending how they play out, could make a difference.

Bumps Along the Road

China. Over the past several months, the market has hung almost obsessively over the latest headline touching on President Trump’s trade battle with China. The slightest rumor of a deal bumps share prices up, while new tariff threats send them reeling—but only for a little while. It’s entirely possible that short-term political considerations could push both leaders to announce an agreement, but investors should be careful this doesn’t blind them to the bigger picture.

The first part of the bigger picture is that China is slowing, for reasons that predate the trade war. China’s over-reliance on credit expansion to over-invest in more and more capacity, resulting in more and more bad debt to be refinanced—is gradually becoming a heavier drag on growth, even if the resulting financial stresses get successfully brushed under the rug. A trade deal won’t change this. In fact, one problem is that—contrary to prior trends—China’s imports are falling faster than its exports, causing its trade surplus to widen. China’s flagging purchases of autos and machinery have hit Germany’s economy hard, pushing its Manufacturing PMI into its deepest contraction (41.7) since June 2009, and its economy to the edge of recession (GDP shrank at an annual rate of −0.3% in Q2). Japan, South Korea, Australia, and others are facing similar pressure. As we’ve noted, the long-overdue shift in China’s economic gears could produce more positive results, but amid rising trade tensions and heated political unrest in Hong Kong, those benefits have been hard to realize.

The second part is that the U.S. and China increasingly appear to be on a broader collision course, whether or not specific trade issues can be resolved. The 2008 financial crisis proved a hidden turning point: many Chinese stopped seeing the U.S. as a model worth emulating, while many Americans soured on the cost/benefit of globalization. The rising wealth and assertiveness of China, along with its turn towards greater authoritarianism under Xi Jinping, compounded this fracture. The shift in attitudes among U.S. policymakers in the past year or so, towards a harder line on China, has been profound. To grasp this, don’t look to Trump’s latest tweet, but to a speech that Vice President Pence gave last October, in which he outlined a host of areas where the U.S. has come to see China not as a partner, or even a rival, but a committed and even existential foe. Markets got a taste of what this could mean this spring, when the Administration slapped a ban on Chinese telecom giant Huawei doing business in or buying supplies from the U.S., and again a few weeks ago, when reports emerged that the White House is considering delisting Chinese companies from U.S. stock exchanges, or even restricting U.S. portfolio investment into China. The future could easily bring more sanctions on Chinese technology companies or even financial institutions, partly as leverage in trade negotiations, partly to “decouple” the two economies as part of what some strategists are already calling “Cold War 2.0”. Nor does this necessarily depend on President Trump being reelected. The shift is bipartisan: Democratic candidate Elizabeth Warren’s stance towards China has been just as bellicose. It’s entirely possible the 2020 election turns, in part, into a contest over who can sound “tougher” on China. If so, expect more proposals that could rattle markets in the short term, and have a more lasting impact if actually implemented.

Brexit. Divided over how to proceed, unhappy with the terms it could get from the European Union, Britain postponed its original exit date from the E.U. this spring. Now, like a feckless college student granted a term paper extension, it has frittered away the extra time it begged for and finds itself back in the same predicament, with time again running out. The process—which included a failed attempt to keep Parliament from meeting—has become so confused and complicated that even many serious observers have shrugged their shoulders and checked out. But the clock is ticking. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who replaced Theresa May in July, declares he’d rather “die in a ditch” than request another delay, and if that’s true, the U.K. will be out of the E.U. on Halloween, deal or no deal.

The impact on the U.K. economy, so far, has been surprisingly mild. Britain’s GDP fell at an annualized rate of −0.8% in Q2, its first quarterly decline since 2012, but Q3 is expected to see a rebound (and dodge a recession). But small businesses, in particular, have been reluctant to devote precious resources to prepare for a no-deal Brexit that may or may not happen, leaving them potentially vulnerable. Retailers are divided over whether they should stockpile food and items that might see supply disruptions. European countries have stepped up plans to deploy hundreds of new customs officials and extend residency permits for U.K. citizens, but no one really knows if these measures will prove adequate—or even necessary. The toughest problem is still where and how to place the customs border between Ireland and the U.K., a circle nobody has been able to square, and a no-deal Brexit does nothing to solve.

A “no deal” Brexit sounds like it cuts the Gordian Knot, and—for better or worse—allows everyone to move on, but it doesn’t. Instead, Brexit is looking more and more like a saga that will go on after October 31, without a clear resolution, even if Britain does leave. That’s worrisome for a Europe already wobbling on the edge of recession, where political legitimacy is already feeling strains. Even if “Brexit Doomsday” scenarios involving stranded shipments and empty shelves are grossly overplayed—and we suspect they are—it’s a set of uncertainties nobody really needs right now, but nobody knows how to clear up.

Impeachment. The political storm in DC reached a new crescendo in recent days as whistleblower allegations concerning a presidential phone call to Ukraine prompted House Democrats to begin impeachment hearings aimed at removing President Trump from office. With polls showing the public equally divided between removing the president or not, a contentious battle is set to consume the next several weeks and months. President Trump warns that any attempt to remove him would crash the stock market, and it’s reasonable to look back at past impeachment episodes to ask how such a heated and high-stakes fight is likely to affect investors.

From the time the Watergate scandal first burst onto the scene in February 1973, to the day President Nixon resigned in August 1974, the S&P 500 fell −29%. But Nixon’s travails coincided with a sharp deterioration in the U.S. economy, and the market’s big tumble came with the Arab Oil Embargo, which quadrupled oil prices. Nixon’s job approval rating collapsed with the economy, bottoming out around 25% more than a year before impeachment reached its climax. The day Nixon stepped down, the U.S. was in the first quarter of a recession and experiencing double-digit +11.5% inflation. Evidence of wrongdoing aside, it’s not hard to imagine that people’s existing dissatisfaction helped seal the president’s fate.

In contrast, President Clinton enjoyed job approval ratings of 60–70% through most of his impeachment saga, buoyed by steady economic growth and low inflation. The S&P 500 rose +28% from the day the Lewinsky scandal first came to light in January 1998, to the president’s trial and acquittal by the Senate a year later. Their rise was briefly interrupted by a sharp −19% correction that coincided with the president’s grand jury testimony and public confession. But the downturn was mainly driven by the Russian ruble crisis and the near collapse of a large U.S. hedge fund (LTCM), and stocks rebounded once the financial crisis had passed. At the time, Clinton’s supporters explicitly pointed to good economic times and the president’s resulting popularity as reasons why the (admitted) charges against him didn’t merit his removal.

Our takeaway is that while impeachment can rattle markets, the market’s overall direction is tied to the economy, and the economy’s performance may be more likely to influence the political outcome than the other way around. Therefore, we will continue to keep our eyes on the fundamentals.

It’s All Relative

Investors might find all of this rather daunting and be inclined to reduce their exposure to risk. But the truth is that—despite the unsettling risks they face, despite the possibility of the current slowdown turning into a recession—the relative pricing of safety and risk in the market right now still favors accepting risk, to the extent they can afford to.

So far this year, the S&P 500 has generated total returns (including dividends) of +20.6%. Its shares may look pricey at a 12-month trailing P/E ratio of 19.3x earnings, especially given all the vulnerabilities and uncertainties we’ve just discussed. But the implied P/E ratio for the 10-year U.S. Treasury yielding 1.68% per annum (barely tracking inflation) is 60x, and even hit 68x (1.47%) in early September, while nearly $15 trillion of global bonds are generating negative yields. That’s kept the equity risk premium at 5.6%, still well above its long-term average of 4.2%, compared to just 2.0% at the peak of the dot-com craze. A risk premium that high—as we’ve noted before—is historically correlated with above-average equity returns over the following five-year period.

What happens in the meantime? Investors need to keep in mind that all recessions—and their impact on markets—are not created equal. The last U.S. recession, in 2008, lasted six quarters—a year and a half—followed by an equally painful downturn in Europe. Starting in late 2007, the S&P 500 tumbled −57%, and took over five years to recover lost ground. The 1990–91 recession, however, played out very differently. It lasted three quarters—half as long. The S&P 500 initially fell −20%, but even before the recession was over, seven months later, the stock market had bounced back fully. Though we are keeping our eye out for bigger risk factors, the data right now suggests that—if a recession does occur—it is likely to be a relatively milder, shorter one. By the time recessions like that take hold, markets are already beginning to look through them towards the recovery to follow.

This is what we mean by saying investors should resist the urge to crouch down, despite a natural fear of heights. The markets will see ups and downs in the months and years ahead. Some of these twists and turns may even be unnerving. But precisely because they are unnerved, many investors are paying too dearly for a safe refuge from risks they would be better rewarded, over time, for riding out.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Chovanec. No part of Mr. Chovanec’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC