Since 2020, inflation has been top-of-mind for households worldwide. Usually, consumers only notice inflation when it hurts their wallets, but many organizations and professionals monitor it constantly—whether inflation is calm or volatile. One such organization is the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed). On its website, the Fed states that it “conducts the nation’s monetary policy to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates in the U.S. economy.” When measuring the overall health of the economy, investors, economists, and policymakers pay close attention to inflation because it affects many critical components. Interest rates and monetary policy, currency value and exchange rates, consumer spending, and corporate earnings are all largely driven by it, and perhaps most important to an investor is that nearly every investment analysis factors in inflation as a baseline for its required rate of return.

Despite its significance, inflation is not easily measured. While it is typically calculated on a broad basis, it can be measured more granularly for specific goods and services. This is done not because of a difference of opinion between statisticians but rather in an effort to better understand a complex concept from multiple angles. This explains why the Fed, as the shepherds of monetary policy, relies on a broad range of data points to assess inflation properly. That being said, news articles often refer to the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE) as “the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation.” Why is this?

How We Gauge Inflation

The two primary gauges of inflation are the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE).

The two primary gauges of inflation are the Consumer Price Index (CPI), released monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE), also released monthly by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Most of the time, when someone refers to an outrageous inflation stat in casual conversation, they are referring to CPI. Because of this publicity, CPI is the more commonly known measure of inflation. CPI calculates the average change in prices paid by consumers for a weighted market basket of goods and services. The weighting system ensures that sharp price increases in low-impact items, like vending machine snacks (weighted at 0.05%), barely affect the index. In contrast, even modest increases in high-impact items, such as gasoline (weighted at 3.26%), have a significant effect. The goal of CPI is to capture changes in out-of-pocket spending by urban consumers to help provide a reliable and comprehensive measure of inflation that can support monetary and fiscal policy.

To do this, BLS employees collect pricing data on an extensive array of roughly 80,000 items. Many people have seen the graphics of the price of eggs trending higher since 2020, but the list also includes rent and even computers, televisions, and clothes. Basically, any item a typical American household might purchase is tracked. To gather the pricing data for each item, BLS data collectors go through a laborious process each month, obtaining the pricing information through in-person visits, websites, applications, or by calling thousands of retail stores, service establishments, rental units, and doctors’ offices across the country. By surveying this information on a monthly basis, price changes can be tracked and measured.

PCE—the lesser publicized metric—has been considered the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation since 2000. PCE reflects the prices paid by households and on their behalf. This differs from CPI because it includes third-party payments like employer-provided healthcare and government benefits. The goal of PCE is to measure inflation accurately by tracking changes in the prices of goods and services consumed by households, helping assess the increase or decrease in the cost of living over time.

PCE pricing data is collected through a variety of data sources, which aim to make a comprehensive measure of inflation. It is less dependent on self-reported consumer surveys, relying more on business surveys and administrative records from various government agencies.

Differences in Methodology

Historically, CPI and PCE tracked each other closely. However, over longer periods of time, and especially more recently, the two measures have deviated from one another due to several essential differences within their methodologies. So, what’s behind this trend, and why has it caused the Fed to favor PCE?

- CPI and PCE are constructed using different mathematical formulas. CPI uses the Laspeyres formula, while PCE uses the Fisher formula. Although both formulas measure how a price level changes over time, there are some key differences in their calculations that lead to divergence. The Laspeyres formula measures how prices change over time for a fixed set of goods and services from a starting period. In contrast, the Fisher formula takes a more flexible approach. The key advantage of the Fisher formula is that it accounts for substitution bias. Substitution bias happens when people change what they buy in response to price changes, like choosing chicken over beef if beef becomes more expensive. The Laspeyres formula doesn’t capture this shift because it sticks to a fixed basket of goods, making it less reflective of real consumer behavior. With its more dynamic approach, the Fisher formula adjusts for these changes, providing a more accurate picture of how prices impact consumers.

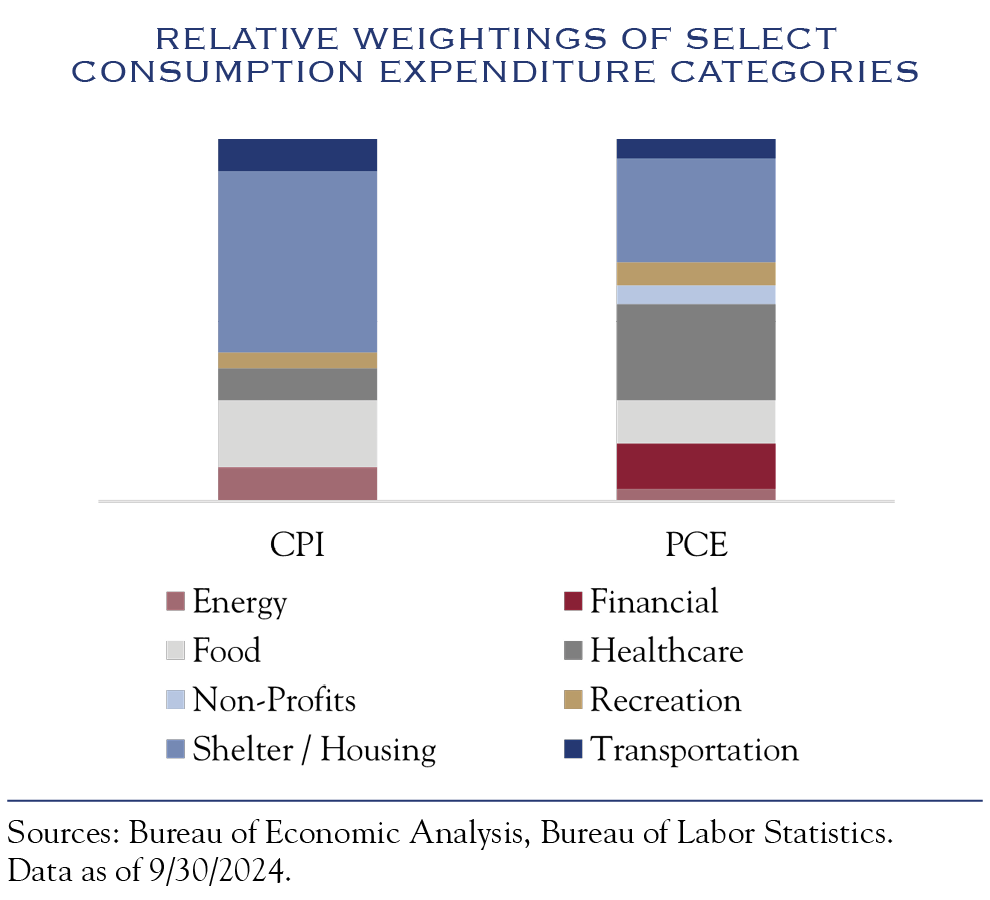

- CPI and PCE differ in how they are weighted. Since the collection methods and responses vary, CPI is only weighted annually using the consumer expenditure data from the two previous years, while PCE is weighted monthly. This frequent weighting makes the PCE much more dynamic in determining which goods are driving inflation, which has caused the spread between the indicators. Some weighting differences between the two indicators are slight, while others, like Shelter, Healthcare, Transportation, and Food, show much wider dispersion.

- CPI and PCE differ in their scope. CPI only tracks spending in urban areas, excluding rural consumers, and only accounts for out-of-pocket spending of those urban consumers. On the other hand, PCE includes purchases made by both urban and rural consumers, non-profit institutions serving households, and local government expenditures. Therefore, by including more items and expenditures, PCE tends to give a clearer picture of the overall expenses paid for by the consumer.

- The last difference worth noting is the variance in seasonal adjusting methodologies. While both CPI and PCE are adjusted for seasonality, CPI’s adjustment tends to be more volatile due to its infrequent reweighting of categories. PCE, being the more frequently reweighted, often displays smaller blips in its seasonal adjustments as its more frequent updates capture a wider array of consumer spending patterns. For PCE, there is also the added benefit of retroactive revisions, while CPI is generally revised just once per year.

While both CPI and PCE offer valuable insights into inflation, the Fed favors PCE for its broader scope, dynamic weighting, and methodological flexibility. By incorporating a wider range of data sources and capturing a more comprehensive picture of consumer expenditures, PCE provides the Fed with a clearer view of actual cost-of-living changes and consumer behavior trends. The Fed’s reliance on PCE allows it to respond more effectively to inflationary shifts, making it a crucial metric for guiding monetary policy and maintaining economic stability. Nonetheless, despite the Fed’s preference towards PCE, investors must also pay attention to CPI, as it is more visible to the public eye through media and markets and, therefore, serves as a driver of sentiment.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Viscichini. No part of Mr. Viscichini’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC